Three years ago, my mother committed suicide. She didn’t leave a note or a goodbye, but she did leave stuff.

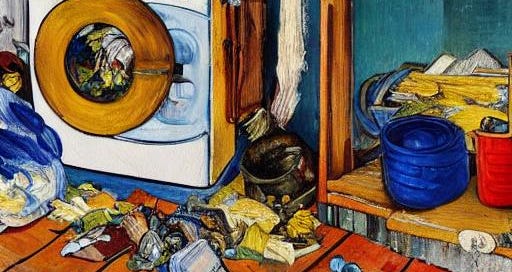

In the main living areas, there were all the things that I’ve come to understand are pretty standard in a hoarder’s home: Piles of plastic bags, waist deep, in what had once been our playroom. Old milk jugs filled with tap water in a bathtub (I still have no explanation for this one). And moving through the rubbish, I remembered that once upon a time, I thought it was normal to keep every phone book that was mailed to you… for the simple reason that my family had about 40.

In the garage, we disposed of boxes and boxes of my grandmother’s medical supplies (she had passed away a decade before, but somehow her prescriptions lingered on…). The storage rooms had boxes that my mother had moved with her from Ohio to Texas 30 years before— I’m not sure whether she had opened them before her move, but she certainly hadn’t opened them in the time I had been alive. And yet, these boxes had made a cross country move, then lived in at least two different storage rooms and three homes in the three decades since. We opened them to find old college notes, mildewed clothes from the 1960s, and more vacuums than people in our family.

The attic, though, was where I began to break. When I was a kid, I used to climb up ladder to sit in the 100-degree attic heat and soak up the silence (a rarity in a home with a mentally unstable parent). I loved poking around what I could see— boxes of Christmas wrapping, an old dollhouse, and jars of spaghetti sauce (doesn’t everyone climb into their attic to get their dinner ingredients?).

But as an adult, crawling deeper into the attic than I had ventured as I child, I felt nothing but anger. I dropped two boxes of brand new school supplies— notebooks, glue sticks, and folders— down to the ground. They had been sitting in the attic for at least a decade— but given that the last time a glue stick was on a school supply list was elementary school, probably far longer. However long it was, the mice had made themselves cozy, their droppings rendering everything in the boxes unusable.

In the next box, I found a miniature American Girl doll— Josefina, to be exact. And my adult heart was completely crushed. Growing up, American Girl was my jam (no thanks to the Mattel takeover, but I suspect that the vibrant historical characters played a role in my later decision to become a historian). I had spent hours pouring over every catalog that came in the mail, checking books out of the library, and finally received a doll from my grandparents when I was 9. Somewhere in my child-hood psychology, I was under the impression that anyone with more than a few AG dolls must be spoiled, but here one was— sitting in my mom’s attic. It had been waiting for me for so long that I was pregnant with my first child when I found it.

And there is the crux of the stuff problem: A doll that’s been forgotten in an attic for 20 years is a waste of money and environmental resources. The ‘holiday’ dishes that get pulled out once a year aren’t earning their keep in your home. And if you’re even considering whether something is trash, it’s probably time to let it go.

And there is the crux of the stuff problem: A doll that’s been forgotten in an attic for 20 years is a waste of money and environmental resources. The ‘holiday’ dishes that get pulled out once a year aren’t earning their keep in your home. And if you’re even considering whether something is trash, it’s probably time to let it go.

Hoarding is a mental illness, and it is not my intention to reduce my mother’s life to nothing but the things she carried with her. Her worth as a human wasn’t measured by the dozens of butter containers in her kitchen any more than your worth is measured by the designer bag on your shoulder. But just as I saw the traumatic effect of excess on my mother’s life, her death offered an opportunity to shine a light on the stuff we carry with us.

We all come with physical baggage. If you walked into my home today, you would find clothes, dishes, books, and toys— though I imagine that, as a long-time minimalist, I have far less than the 300,000 objects that are standard to American homes.

But it’s easy to let the clutter creep in. We justify the “just in case” items— “I’ll keep the second air compressor just in case the first one breaks,” or “I’ll hold onto these jeans just in case I fit in them one day.” And we buy an excess “just for when”— sure, shampoo might be a need, but you probably don’t require 12 extra bottles under your bathroom sink. The physical baggage of just in case and just for when and just on special occasions fills our closets, cabinets, and storage rooms— and the clutter will follow us, in one form or another, until we declutter it or we die.

There are countless benefits to decluttering now instead of later. For one, as I’ve alluded to previously, you don’t want your family members to have to mourn your passing by calling 1-800-GOT-JUNK.

But beyond that, decluttering now makes room for the things in your life that matter most— in other words, the things that aren’t really “things” at all.

A few years ago, my husband stumbled upon a poem that has stuck with me:

Dust if you must, but wouldn't it be better

To paint a picture, or write a letter,

Bake a cake, or plant a seed;

Ponder the difference between want and need?

Dust if you must, but there's not much time,

With rivers to swim, and mountains to climb;

Music to hear, and books to read;

Friends to cherish, and life to lead.

Dust if you must, but the world's out there

With the sun in your eyes, and the wind in your hair;

A flutter of snow, a shower of rain,

This day will not come around again.

Dust if you must, but bear in mind,

Old age will come and it's not kind.

And when you go (and go you must)

You, yourself, will make more dust.Rose Milligan, The Lady (September 1998)

The just-in-case, the just-for-when, the just-on-special-occasions “stuff” takes our most valuable resource: Our time. It takes time to earn the money to buy the “stuff,” time to shop, and time to organize, sort, clean, rearrange, clean again, and, perhaps, time to ultimately declutter.

I don’t know about you, but I’ll take my decluttering now instead of wasting the next half-century dusting “stuff” when I could be living my life.